A recent statement by acting NASA administrator Sean Duffy has sent shockwaves through the aerospace industry. His suggestion that SpaceX could be dropped from NASA’s upcoming moon-landing mission has triggered a flurry of activity as companies scramble to propose alternative ways to reach the lunar surface. Currently, SpaceX holds a $2.9 billion contract to develop its massive Starship rocket system for the Artemis III mission, designed to carry astronauts to the moon. However, amid delays in Starship’s progress and mounting competition from China, NASA has asked both SpaceX and Blue Origin — which holds a separate lunar lander contract — to submit updated plans to speed up development. Both companies have complied, but NASA is also reaching out to the broader commercial space sector, signaling that it might be ready to explore new partnerships altogether. According to sources familiar with internal discussions, the agency is quietly preparing to issue a formal call for proposals once the ongoing government shutdown ends. Several companies have already begun brainstorming ways to accelerate lunar access, though experts warn that developing a new spacecraft from scratch typically takes at least six to seven years. That timeline could jeopardize NASA’s goal of landing astronauts on the moon by mid-2027. China’s goal of placing astronauts on the lunar surface by 2030 adds further urgency. Duffy has repeatedly described beating China to the moon’s south pole as a matter of national pride and security. That region — rich in ice and sunlight — is considered the most valuable real estate on the moon for future human settlement and resource development.

Inside NASA’s High-Stakes Push for a New Moon Mission Plan

SpaceX’s Starship is widely known as the most powerful rocket system ever built. The company has conducted 11 suborbital test flights, achieving milestones such as booster reuse and successful engine restarts in space. SpaceX claims to have completed 49 of its contracted milestones for NASA, covering key systems, infrastructure, and operational requirements. Despite these accomplishments, the Starship program has been plagued by setbacks. In early 2025, three test vehicles exploded during flights, and another ignited on the ground, damaging facilities in Texas. These incidents have fueled concern among U.S. officials that Starship might not be ready in time for NASA’s schedule. Under the current mission plan, NASA astronauts will launch aboard the Orion spacecraft, which sits atop the Space Launch System rocket. After reaching lunar orbit, they will transfer to Starship, which will take them down to the surface and then back into orbit. But Starship has yet to fly a fully orbital mission or demonstrate in-space refueling — a crucial step given its enormous fuel demands. Estimates suggest between 10 and 40 tanker flights may be required for a single moon mission. Transferring cryogenic propellants in space has never been done before, making this a major technical hurdle. Former NASA officials, including Doug Loverro, have warned that SpaceX may not achieve full readiness before 2030. The company has not released detailed plans on how it intends to accelerate progress.

Blue Origin’s Backup Option

One alternative Duffy mentioned is Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lander. Funded by Jeff Bezos, the company already has a contract to supply landers for later Artemis missions, including Artemis V. Because of its existing relationship with NASA, Blue Origin might represent the quickest path to a backup plan. The company is developing two models: Mark 1, for cargo transport, and Mark 2, designed to carry astronauts. To adapt for Artemis III, Blue Origin is reportedly considering a hybrid design that combines elements of both. The proposed system would use one or more Mark 1 landers as rocket stages to push a smaller Mark 2 out of Earth’s orbit and toward the moon. While this approach would still require multiple launches, it avoids the complexity of in-space refueling that Starship demands.

Lockheed Martin’s Modular Proposal

Lockheed Martin, a long-time NASA partner and the builder of the Orion spacecraft, is also preparing to present a new lunar lander concept. The company’s design would use existing hardware from Orion, including the same OMS-E engines, for the ascent stage that lifts off from the lunar surface. For the descent stage, Lockheed plans to partner with another commercial company, though it has not yet chosen which. The company is considering two design paths: a cryogenic-fueled system similar to Blue Origin’s or one using hypergolic propellants, which are easier to store and handle in space. If Lockheed selects the cryogenic option, the lander’s stages would need to launch separately and dock in orbit before heading to the moon. If it uses hypergolic fuel, the entire vehicle could launch in one piece and be refueled in orbit — a process NASA and its partners have mastered since the early days of the International Space Station. Lockheed argues its approach would be faster than SpaceX’s or Blue Origin’s because it relies on proven hardware and avoids untested technologies like cryogenic refueling.

Other Contenders and Challenges

Other aerospace firms, including Firefly Aerospace and Northrop Grumman, have expressed willingness to support NASA’s lunar goals but have not confirmed whether they will submit full proposals. Experts say NASA should consider tapping its own resources, including the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), to play a more central role in designing a new lunar lander. JPL, known for robotic missions such as the Mars rovers, has decades of experience managing complex engineering projects on tight timelines. Though not traditionally focused on human spaceflight, its expertise in systems integration and rapid innovation could help NASA meet its deadlines. However, every new plan faces two major obstacles: cost and time. SpaceX’s Starship remains the most cost-effective option because the company is privately funding roughly 90 percent of its development. Other proposals would likely require billions in new federal funding at a time when NASA’s budget is already stretched thin. Even with strong political support for the Artemis program, analysts question whether Congress would allocate more money to start over with a new design. Some experts argue that beginning a new lander project now might actually delay the mission further — possibly by several years.

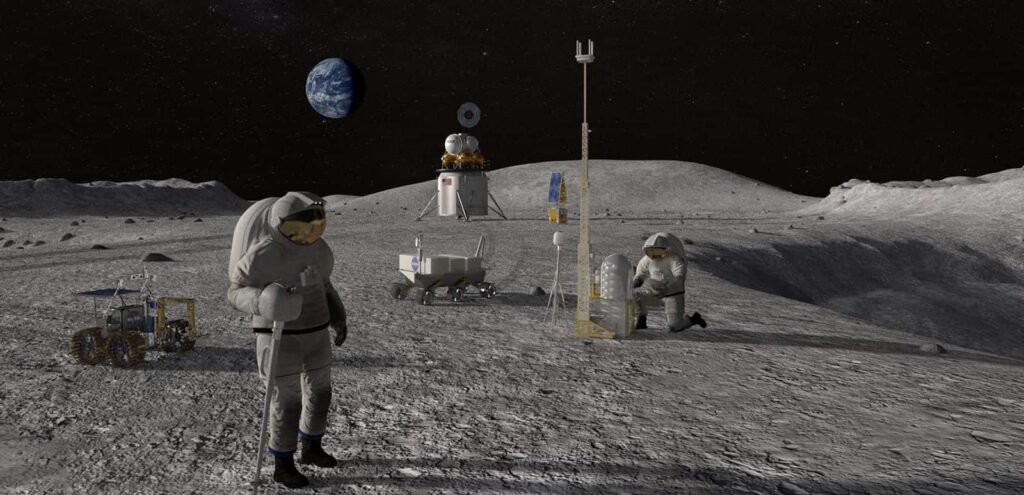

A Broader Vision Beyond the Race

While the push to return humans to the moon has been framed as a modern space race against China, many within NASA and the scientific community argue that the ultimate goal should go beyond symbolic first steps. Establishing a sustainable lunar base where astronauts can live, work, and test technologies for future Mars missions could offer far greater long-term benefits. SpaceX has echoed that sentiment, stating that Starship is not just a vehicle for landing astronauts but a key enabler for creating lasting infrastructure on the moon. With its enormous cargo capacity, the spacecraft could deliver equipment, habitats, and supplies in unprecedented quantities. In the end, the true measure of success for NASA may not be which nation lands first, but which can build the foundation for a permanent human presence on another world. As the agency considers new proposals and reevaluates existing contracts, one thing is clear — the next few years will define not only the future of lunar exploration but also NASA’s place in the evolving era of space competition.